Map of Eritrea

Location and geography

Eritrean history

Border conflict with Ethiopia

Political structure

Eritrean anthem

Economy & currency

Climate

People

Languages

Religion

Health care

Transport

Cuisine

News, links, books and more

Asmara (Asmera)

Agordat (Akordat)

Assab (Asseb)

Barentu

Dahlak islands

Dekemhare

(Decemhare)

Ghinda (Ginda)

Keren (Cheren)

Massawa (Massauwa)

Mendefera (Adi

Ugri)

Nakfa (Nacfa)

Semenawi Bahri (Filfil)

Tessenei

(Teseney)

Background to the border dispute between Eritrea and Ethiopia

by Hans van der Splinter

After 1991 (victory of the Tigray Peoples Liberation Front (TPLF) on regime of Mengistu Haile Marian) many former Ethiopian guerrillas have moved into the Badme region to farm small plots of land, displacing many Eritrean farmers who were already there. This process slowly resulted in Ethiopian domination over these Eritrean territories, forceful eviction of Eritrean farmers from their properties and looting of their animals. In August 1997, Ethiopian troops occupied the Eritrean village of Adi Murug under the pretext of pursuing "terrorists". In the same month Ethiopia expelled Eritrean citizens from their homes around Badme. These expulsions and the destruction of crops and other property continued throughout the next year. Two rounds of fighting followed in 1998 and 1999.

In May 2000 a frustrated Ethiopia launched a full-scale invasion into western and central Eritrea, aiming at maximum economic destruction, destroying newly constructed plants, offices, hotels and residences. Having re-captured Badme and other disputed areas, and under considerable pressure from the international community, Ethiopia halted its advances and both sides signed a cease-fire on June 18th 2000. Six months later a final peace treaty was signed, with both countries agreeing to resolve the dispute through binding international arbitration.

The new Tigray map

Ethiopian territorial claims are based on a recently published new map of the Tigray administrative zone. In the map shown below the new 1997 Ethiopian map (f.e. as posted by the Ethiopian Embassy in Sweden and the National Electoral Board of Ethiopia) is superimposed on the map of Eritrea in the CIA fact book of Eritrea. It can be easily seen that by drawing this new map Ethiopia is administratively occupying a part of Gash Setit and parts of Akule Guzai, violating the legal borders, established by treaties signed with Italy in 1900, 1902 and 1908. (anyone can compare this new Tigray map to any other map on the internet and simply verify it is a fabrication of the Ethiopian government, see e.g. the "political map of Ethiopia" used in Ethiopian geography books in the 70's).

Proof of Ethiopia's illegal map

These overlapping areas in Gash Setit and Akule Guzai were then 'occupied' by Eritrea in May 1998 and are referred to as the Badme and Zalambessa front. But whereas Ethiopia is demanding to return the 'occupied' territory, Eritrea is only defending her legally established border!

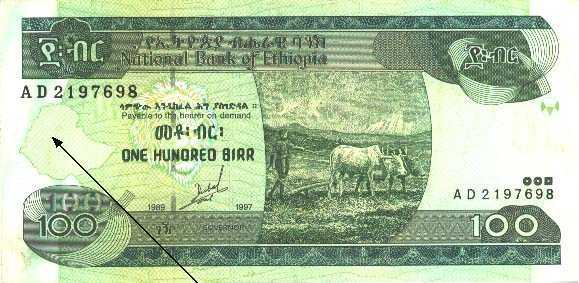

Subsequently Ethiopia embossed this new change in its new currency notes issued in November 1997. The arrow on the Ethiopian 100 birr note below points to the 'new' Ethiopian map. A similar impertinent reclamation of land will not be easy to find in the worlds history.

Outline of 'enlarged' Ethiopia on a 100 birr note (1997).

So the aggression, although first 'administrative' was initiated by Ethiopia. Ethiopia continued to demand that Eritrea must unilaterally and unconditionally withdraw from the areas Ethiopia claims, and that Ethiopia administers these areas as a precondition. If not, it goes to war.

The first victims of Ethiopian aggression were the groups of Eritrean peasants who were displaced by Ethiopian milititia. Unarmed Eritrean colonels were sent to negotiate with the local officers in Badme. They were welcomed with gunfire and shot in cold blood. And on May 6, 1998 Eritrea re-captured Badme and reversed the Ethiopian aggression. So, here we see a thief (Ethiopia) threatening the legal owner, who is protecting his property (Eritrea).

Eritrea's position has been for a quick demarcation of the border by a mutually acceptable technical team in the presence of a third party to witness the process and to act as a guarantor of the outcome.

The manifesto of the TPLF on 'Republic of Greater Tigray'

The new map of Tigray is based on the 1976 TPLF (*) manifesto, which defined who a Tigrayan is, the land that the TPLF considers of Tigray, and the final destination of the TPLF. The following comprises some important contents of the manifesto.

- A Tigrayan is defined as anybody that speaks the language of Tigrinya including those who live outside Tigray, the Kunamas, the Sahos, the Afar and the Taltal, the Agew, and the Welkait.

- The geographic boundaries of Tigray extend to the borders of the Sudan including the lands of Humera and Welkait from the region of Begemidir in Ethiopia, the land defined by Alewuha which extends down to the regions of Wollo and including Alamata, Ashengie, and Kobo, and finally the lands of Eritrean Kunama which includes Badme, the Saho (close to the conflicting area of Zalambessa) and Afar lands including Assab.

- The final goal of the TPLF is to secede from Ethiopia as an independent 'Republic of Greater Tigray' by liberating the lands and peoples of Tigray.

Proud of the fact that the founding Ethiopian empire, Aksum, was centered in Tigray, and wary of the historic dominance of the Amhara, many Tigrayans today continue to assert their ethnic separateness. The TPLF manifesto is of the same tenor as the German manifest on 'das Gross Deutsche Reich' just before WW2. It likewise bases territorial claims on the assumption that border corrections are justified to incorporate 'its' people into a newly defined (read: enlarged) state.

Implementation of this manifesto (the so called TPLF 'hidden agenda')

"I was picked up at night, thrown into prison, not allowed time to pack. I asked what my crime was. 'You're an Eritrean,' they said." (Amnesty International)

- started in 1992 when Ethiopia was divided in 7 ethnic regions (and Tigray expanded its territory with 60% (!) by trimming fertile land from Beemer and Wollo).

- was followed by the 1994 adjustment of the Ethiopian constitution, allowing every ethnic region to secede on grounds of self-determination

- and the 1996 pull out of Eritrean troops from Ethiopia (which until that time supported TPLF forces to stabilize the Ethiopian federation) on request of the TPLF based government

- resulting in the 1998 occupation, both administrative and by force, of Eritrean territory and deportation of 75,000 ethnic Eritreans, mainly from Tigray and Addis Ababa.

(*) Tigray Peoples Liberation Front

The free port of Assab

Red sea port Assab has played an important role in the negotiations between Italy/Eritrea and Ethiopia. Emperor Melenik II did not demand access to the port. He did not want to be dependent on Italy and made a treaty with France in 1897. One of the things that were arranged in this treaty was that a railway was to be build from the port of Djibouti in French Somalia to Addis Abeba. In 1917 the first trains were running. The railway was sufficient for the modest Ethiopian imports and exports.

In 1928 Emperor Haile Selassie made a treaty with Italy and Ethiopia got a free zone in the port of Assab. A road was to be build between Assab and Dese in Ethiopia.

When the railway to Djibouti was blown up at several places in the war with Somalia, Assab became Ethiopia's most important port. Especially because Ethiopian rebels kept sabotaging this railway.

In 1991 (after having ousted Mengistu), liberated Eritrea got nearly exclusive control over Ethiopia's access to the sea. In the negotiations between Eritrea and Ethiopia, Eritrea guaranteed that Ethiopia could use the port of Assab on the same terms as Eritrea itself. This has some logic since Assab is 750 kilometer from Asmara and the core regions of Eritrea which are served by the port of Massawa. In the meantime Ethiopia is reconstructing the railway to Djibouti with French help.

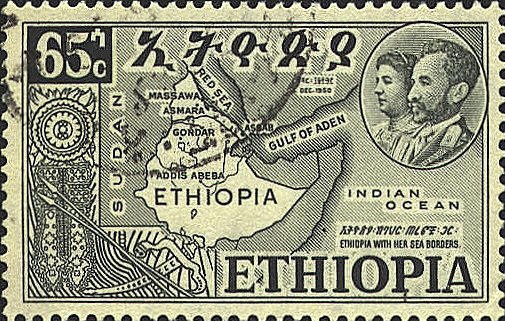

Celebrating Ethiopia’s federation with Eritrea Ethiopia issued nine stamps in 1952.

One of them features a map of the Horn of Africa and the Arabian peninsula, entitled:

"Ethiopia with her Sea Borders".

Part X of the Law of the Sea Convention provides the terms and conditions by which landlocked states and their coastal neighbors could and should operate. Landlocked states like Ethiopia have rights of access. But the coastal state does not have to surrender part of its sovereign territory. Ethiopia should not try to be above the law or consider itself a special state with natural rights to its own seashores.

Ethiopians note that it is inequitable for Eritrea, to retain two ports while the larger and densely populated Ethiopia remains landlocked. Ethiopia is not the only land locked country in Africa. In Africa only there are more than twelve land locked countries besides Ethiopia while there are five in Europe and six in Asia. What problem are they facing? As far as we know virtually nothing. They are not suffering any adverse consequence as a result.

Other Ethiopian arguments to take Assab by force are rooted in the belief that the Afar people living in this area should be reunited with the Afar people living in Ethiopia. This argument goes further than claiming parts of Eritrea. It also means claiming parts of the former French colony Djibouti. These claims however are contradictory to the 1964 OAU Summit in Cairo:

" .... the parties reaffirm the principle of respect for the borders existing at independence as stated in resolution AHG/Res. 16(1) adopted by the OAU summit in Cairo in 1964, and, in this regard, that they shall be determined on the basis of pertinent colonial treaties and applicable international laws"

This Ethiopian argument would undermine virtually every border on the African continent, including Ethiopia's own borders with other neighboring countries (Kenya, Somalia, Djibouti and Sudan).

Main ports in the horn of Africa

Ethiopia's five outlets to the sea.

Trade between the two countries has come to a halt due to the conflict. Ethiopia has yet to suffer shortages or significant price rises as a result of using ports other than Assab for its supplies. It looks like the Ethiopians have miscalculated the time it would take to end the conflict in their advantage and are now de facto landlocked as a result of their own aggression.

Ethiopian investments in the past will be worthless as long as they cannot use the port of Assab. That is the reason why Ethiopia is trying to fight itself a corridor to Assab, to conquer "their" main port (the third front), brutal Red Sea lust. Why not use the ports of Djibouti, Sudan, Kenya, Somalia? To expensive? Do the conditions not satisfy them? So if I find the airfare of Ethiopian Airlines to expensive it is justified to hijack the plane?

The real reason for the Ethiopian (read TPLF) efforts to control Assab may very well be the fact that the only asset now landlocked Tigray is missing to declare independence is a port.

Ethiopia however prohibited both currencies to circulate freely in both countries, insisting that for all but small local trading (all trade transactions in excess of US $250), hard currency should be used which both sides lacked. This Ethiopian arrogance further disrupted trade between Ethiopia and Eritrea. The new policy effectively banned cross-border livestock exports by farmers and small traders, leading to depressed livestock prices and trucks soon were backed up at border crossings, while ships waited to unload at Assab.

In consequence of this new Ethiopian cross-border trade regulations, the control of borders, as well as their position suddenly became a matter of importance, where the exact position of the frontier had previously been of little significance to the local population.

The intertwining history

Supporters of a united Ethiopia and Eritrea emphasize the intertwining history of these two countries. But no country in Africa has an homogenous population, where all speak the same language, practice the same religion and share a common history and culture. Boundaries were imposed upon the continent by the European powers in their scramble for Africa during the 19th and 20th century, but are generally respected by the now independent countries.

While it is true that strands of Eritrean and Ethiopian early history intermingle, particularly under the highland kingdom of Axum, it generally manifested itself with Ethiopian rulers exercising authority over and making periodic excursions into Eritrean lands to collect slaves, plunder and rape. In May 2000 history repeated itself (destruction and ransack of Barentu and Tessenei by the Ethiopian "defense forces").

Shop, plundered by Ethiopian soldiers. Shortly before the looting,

the owner was killed by Ethiopian soldiers in Sheshebit, some 10

kilometer from Shilalo. (from: Berhe's picture book - B. Berhane).

It was the fifty years of Italian rule that irrevocably separated Eritreans from Ethiopians. Under the Italians, Eritreans made great strides into the twentieth century, that left them better educated and more sophisticated than their neighbors to the feudal south. The Eritreans began to develop a collective consciousness of being a people with a connected past and a common destiny and the Eritrean nationalistic culture was born.

But Eritrea exists not only by virtue of Italian creation but also by an explicit Ethiopian renunciation. The relatively modern concept of an Eritrean national identity grew its deepest and most intractable roots during thirty years of Ethiopian cruelties of occupation, after Eritrea was forcibly annexed by Ethiopia's Haile Selassie in 1962. Ethiopian rule was a continuation of colonialism and has accelerated the formation of national consciousness. EPLF could not have survived without a broad base of support among the population or without a deep-seated resentment against Ethiopian domination.

"It was at 10:00 a.m. on May 24, 1991 that Asmara residents realized EPLF fighters had entered their city. In a spontaneous outburst of happiness and relief, Asmarinos flung open their doors and rushed into the streets to dance in jubilation, some still in their pajamas. The dancing lasted for weeks."

In April 1993 a referendum was held in which 99.8% of the Eritrean population voted for national independence.

Imperialistic tendencies of Ethiopia

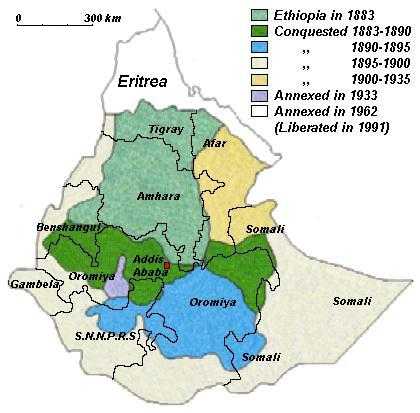

The abstract concept of a Greater Ethiopia has always been a powerful source of pride and yearning of Ethiopian rulers. May the map presented below speak for itself as an illustration of Ethiopia's growing pains of the last age. I found it in a German history book published in 1978 (A. Bartnicki and J. Mantel-Niecko, Geschichte Äthiopiens). I have added the names of the present Ethiopian administrative regions to the map. The map is the very convincing proof that Ethiopia is entertaining secret ambitions to expand.

History of Ethiopian imperialism 1883-1991

The recent Ethiopian expansion resulted in a deeply divided and demoralized state, many ethnic liberation movements and internal political tensions. Power rests on the Amhara and Tigray community which are still in the process of establishing dominance over the entire territory of the state. Oromo and other tribal opposition is "controlled" by employing troops from these regions in the war against Eritrea, where they either slaughtered by Eritrean or by their own troops. It is likely that the territorial unity of this unhappy, famine- and war-wracked country is at serious risk.

Ethiopia wants to project an image of a regional power and impose its will on its neighbors, which will be very difficult on an empty stomach.

When will this war end?

The increased popularity of Meles Zenawi (Ethiopia's Prime Minister) in Tigray and Amhara because of this war makes it hard for him to stop the fight. He and his TPLF clique might not survive a peace that gave Ethiopia only little gain. The expected result of Ethiopia's recent adventure of expansionism is far less than they calculated on forehand. It may therefore be expected that the stake will be higher and higher before the negotiations start as not to disappoint his Tigrayan supporters. Meles Zenawi is now demanding that his territorial claims will be guaranteed before negotiations can take place. This has to be Ethiopia's arrogance to the fullest sense!

He might even wait for Eritrea to bleed to dead, hoping it will be the end of Isaias Afwerki, who once was a close personal friend and brother in arms when Eritrean and Tigayan Liberation movements fought side by side against the Dergue (the Amhara based ruling committee in the 70's and 80's) resulting in Eritrea's liberation and TPLF control over Ethiopia. The price of Meles Zenawi's 'victory' will be paid by the more then 11 million people in Tigray and Wollo who are at the brink of starving to death in the meantime.

But ironically the war has strengthened the position of Isaias Afwerki, as wars usually unifies nations. Eritrea has accepted an OAU peace plan under which both countries would withdraw from disputed territory, but Ethiopia has questioned the technical arrangements, thereby continuing to sabotage the peace process. True stability can only come in the Horn of Africa if Ethiopia will show real commitment to peace.

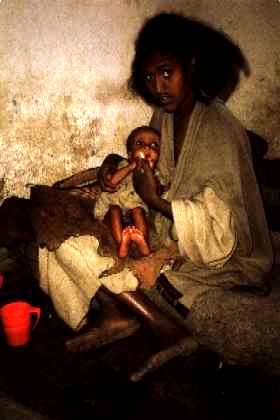

Women and children waiting for food rations in Ethiopia's famine threatened Tigray region. More than 11 million people in Ethiopia (including 1,920,000 children under five years of age, 960,000 pregnant or lactating women) continue to be at risk. source: Unicef (April 17 2003)

"Men with legs and arms as thin as twigs, ribs protruding like grates. Mothers offering shrunken breasts to children too weak to cry or brush flies from their faces. Eyes which, as long as strength remains, show their despair, and once strength is gone, show no emotion at all. These are the faces of the thousands of Ethiopians who sit quietly waiting for the slow death that will surely come to them and to those they love." History will hold the TPLF regime responsible for the death of millions of their people. Unless the rest of the world applies pressure on Ethiopia to make peace, the war looks set to continue. The rest of the world should make it clear to Ethiopia that it is better to feed ones people than squander resources to war.

The world should stop its financial contributions to Ethiopia now that the money is used to engage in an armed conflict instead of development and nutrition of its people.

Decision regarding delimitation of

the border between Eritrea and EthiopiaOn April 13th 2002 the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague published the conclusions of the Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission. The court concluded that a large part of the Western border sector will be awarded to Eritrea (near the Yirga Triangle). Areas in the Central zone and Eastern Sector and border town Tserona have also been awarded to Eritrea. The border towns Zalambessa and Alitena (Central Sector) and Bure Danakil Depression) were awarded to Ethiopia. Despite Ethiopian claims of victory, the border commission rules that the controversial town of Badme, the site of the first flare-ups in 1998, lies in Eritrea.

18. ........Since Badme village (as opposed to some other parts of the Badme region) lay on what was found to be the Eritrean side of the treaty line, there was no need for the Commission to consider any evidence of Eritrean governmental presence there, although Eritrea did in fact submit such evidence. Moreover, even some maps submitted by Ethiopia not only showed the distinctive straight line between the Setit and Mareb Rivers, but also marked Badme village as being on the Eritrean side of that line. The Commission must also observe that the Ethiopian invocation of the findings of the OAU in respect of Badme in 1998 (Comment, para. 1.4, footnote 4) failed to mention the OAU's express statement that those findings did not "prejudge the final status of that area which will be determined at the end of the delimitation and demarcation process and, if necessary, through arbitration."

Eritrea - Ethiopia Boundary Commission - Observations 21 March 2003

Full map of the decisions of the EEBC > > >

Ethiopia hastened to declare that it had won all the land it had claimed, to convince her citizens that the sacrifices and the loss of 150.000 lives have not been in vain.

Chairman Solomon Enkuay, Speaker of the Tigray Regional Assembly, has declared in advance that he would not accept any compromises.

"We shall not accept any decision that attempts to alter the reality on the ground in the face of clear solid evidence. Once more we await justice but we will not be bound by any unjust decision that is based on appeasement and compromise."

The Ethiopian opposition party EDP also announced that it would resist any decision that would not include the transfer of the Eritrean port of Assab to Ethiopia. On 19 May 2002, the opposition Ethiopian Democratic Party mobilized over 10,000 people in Addis Ababa main square to protest the Court's decision, demanding that the Assab port be included in the Ethiopian territory.

Although Ethiopia has agreed to abide with whatever decision is arrived at by the International Court (Article 4.15 of the Algiers Agreement explicitly states that the decision is final and binding), in a surprise turn, Ethiopia rejected the EEBC ruling as "unjust and illegal" and filed a 21-page memorandum demanding that the boundary commission rectify boundary delimitation by redrawing the boundary to give Ethiopia sovereignty over towns on the Eritrean side of the line.

The well-considered decisions of the Court of Arbitration in the Hague appears to cut deep in the self-esteem of Ethiopia. Prime Minister Meles Zenawi cannot explain the loss of Badme to his people and sabotages the demarcation of the border on the ground. By initially accepting the international committee's decision on the delineation of the border with Eritrea, Prime Minister Meles Zenawi lost much credibility in the eyes of the TPLF and among the Tigrayan population in Tigray. This pushed him to then harden his tone toward Eritrea and to take control of the TPLF again.

As a result of Ethiopian refusal to abide by the Hague-based Boundary Commission's demarcation of the border, the physical demarcation of border is delayed indefinitely. The beginning of another round of Ethiopian excursions excursions into Eritrean lands?

On November 25th 2004, 957 days after the EEBC ruling, Ethiopia's parliament voted to accept in principle the ruling of the independent boundary commission that ceded territory along the 600 mile border to Eritrea, after a surprise about-face by Prime Minister Meles Zenawi.

Ethiopian Information Minister Bereket Simon urged Eritrea, one day later to accept the peace plan, but cautioned it must be accepted in total or not at all. "Eritrea must accept the peace plan as a package to end the deadlock along the border between the two neighbors"

The plan calls for a dialogue about the root causes of the conflict and how to implement the boundary decision, Ethiopia to pay its dues to the boundary commission and the appointment of liaisons to help administer the demarcation. But Prime Minister Meles Zenawi of Ethiopia also stated "that Ethiopia would consider the possibility of demarcation only on border areas on which there are no disputes."

This is the evidence that proves that Meles Zenawi and the TPLF ruling party have not unequivocally accepted the EEBC's final and binding decision, and Ethiopia's November 2004 "peace initiative" is more likely an Ethiopian public relations initiative, to buy time and keep up a war of attrition. With the exception of The Netherlands and Sweden, no EU state has pleaded to impose sanctions because of Ethiopia’s refusal to abide the decisions of the Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission.

2012 Ethiopia strikes again

Ethiopian armed forces launched a new provocative attacks on Eritrea as from March 16 2012. This most recent cross-border raids were said to be carried out to eliminate three rebel bases, as Ethiopia spokesmen have confirmed. A number of people were killed and others captured when three camps were attacked up to 18km (11 miles) inside Eritrean territory, an Ethiopian defense official said. Eritrea has said it will not retaliate. "Those who rush to aggression are those who do not know what the life of people means," Eritrean Information Minister Ali Abdu told the BBC.

Ethiopia - a country with rich traditions and outstanding historical and cultural attractions.

3000 years civilization resulting in empty granaries and overstocked ammunition depots.

Statement of the Eritrean government

Asmara, 15-jun-1998

1. The crisis between Eritrea and Ethiopia is rooted in the violation by the Government of Ethiopia of Eritrea's colonial boundaries, and to willfully claim, as well as physically occupy, large swathes of Eritrean territory in the south-western, southern and south-eastern parts of the country. This violation is made manifest in the official map issued in 1997 as well as the map of Ethiopia embossed in the new currency notes of the country that came into circulation in November 1997.

2. Ethiopia went further than laying claims on paper to create a de facto situation on the ground. The first forcible act of creating facts on the ground occurred in July 1997 when Ethiopia, under the pretext of fighting the Afar opposition, brought two battalions to Bada (Adi-Murug) in south-eastern Eritrea to occupy the village and dismantle the Eritrean administration there. This unexpected development was a cause of much concern to the Government of Eritrea. Eritrea's Head of State subsequently sent a letter to the Ethiopian Prime Minister on August 16 1997, reminding him that "the forcible occupation of Adi-Murug" was "truly saddening". He further urged him to "personally take the necessary prudent action so that the measure that has been taken will not trigger unnecessary conflict" A week later, on August 25 1997, the Eritrean Head of State again wrote to the Prime Minister stressing that measures similar to those in Bada were taken in the Badme (south-western Eritrea) area and suggesting that a Joint Commission be set up to help check further deterioration and create a mechanism to resolve the problem.

3. Unfortunately, Eritrean efforts to solve the problem amicably and bilaterally failed as the Government of Ethiopia continued to bring under its occupation the Eritrean territories that it had incorporated into its map. Our worst fears were to be realized when on May 6 1998 on the eve of the second meeting of the Joint Border Commission, the Ethiopian army launched an unexpected attack on Eritrean armed patrols in the Badme area claiming that they had transgressed on areas that Ethiopia had newly brought under its control. This incident led to a series of clashes which, coupled with the hostile measures that were taken by the Government of Ethiopia, resulted in the present state of war between the two countries.

4. Ethiopia's unilateral re-drawing of the colonial boundary and flagrant acts of creating facts on the ground are the essential causes of the current crisis. In light of these facts, Ethiopia's claims that is the victim of aggression are obviously false and meant to deceive the international community. Indeed Ethiopia to this day occupies Eritrean territories in the Setit area in the south-western part of the country.

5. Ethiopia's blatant act of aggression is clearly in violation of the OAU Charter and Resolution AHG/RES 16(1) of the First Assembly of Heads of State and Government held in Cairo in 1964. Unless rectified without equivocation, Ethiopia's refusal to abide by the OAU Charter and decisions, and its continued occupation of undisputed Eritrean territory will open a Pandora's box and create a cycle of instability in the region. The acceptance of Ethiopia's logic will not only affect all African states, but will indeed backfire against Ethiopia itself, since its sovereignty over much of its territory, including on the Ogaden, is based on the same principles of international law.

6. A simple border dispute has assumed this level of conflict because of Ethiopia's continued escalation of its hostile and provocative acts. Among these are:

- the declaration of war by Ethiopia's Parliament on May 13 1998;

- the launching of an air strike by Ethiopia on June 5 1998 on Asmara;

- the imposition of an air blockade and maritime access to Eritrean ports trough the threat of incessant and indiscriminate air bombing;

- the mass expulsion and indiscriminate arrests of thousands of Eritreans from Ethiopia.

7. In spite of all these, Eritrea has been restrained and committed to a peaceful solution of the dispute. In this vein, it has already presented constructive proposals (see further). The proposals center on:

- the demarcation of the entire boundary between the two countries on the basis of borders established by colonial treaties;

- the demilitarization of the entire border area pending demarcation;

- the establishment of appropriate ad hoc arrangements for civil administration in populated demilitarized areas in the interim period.

In addition, considering the state of war that exists between the two countries, the Government of Eritrea has been calling - and continues to call - for:

- an immediate and unconditional cessation of hostilities;

- the start of direct talks between the two parties in the presence of mediators.

Picture of Eritrean soldiers at the Mered-Alitena front watching the

border with Ethiopia (Tserona June 1999 - Photo: Arnold Karskens)

Proposal for a Solution Submitted by the Government of Eritrea

Asmara, 15-jun-1998

1. PRINCIPLES

The Government of Eritrea and the Government of Ethiopia agree that they will resolve the present crisis and any other dispute between them through peaceful and legal means. Both sides reject solutions that are imposed by force.

Both sides agree to respect the clearly defined colonial boundaries between them. In this respect, both sides further agree that the actual demarcation of the borders will be carried out by a mutually acceptable technical team. In the event that there is some controversy on the delineation, both sides agree to resolve the matter through an appropriate mechanism of arbitration.

The demarcation of the borders shall be affected speedily and within an agreed time-frame.

Both sides agree to be bound by this agreement.

2. IMPLEMENTATION OF MODALITIES

2.1 The UN Cartographic Unit, or any other body with the appropriate expertise, shall be charged with the task of demarcating the boundary in accordance with existing colonial border treaties.

2.2 The time-frame for the demarcation of the boundary shall be six months. This time-frame may be shortened or prolonged subject to justifiable technical reasons. This requisite time-frame shall be designated as AN INTERIM PERIOD.

2.3 The demarcated boundary shall be accepted and adhered to by both sides.

2.4 If there are segments in the boundary whose delineation is under controversy, the matter shall be resolved through an appropriate mechanism of ARBITRATION.

2.5 The technical details relevant to the practical implementation of the DEMARCATION process shall be annexed to the agreement.

3. DEMILITARIZATION as a measure for defusing the crisis and expediting the demarcation of the borders so as to ensure a lasting solution shall be accepted and adhered to by both sides.

3.1 DEMILITARIZATION shall begin by the Mereb-Setit segment; proceed next to the Bada area and be implemented throughout the entire boundary in accordance with this phased pattern.

3.2 DEMILITARIZATION shall be implemented trough the involvement and monitoring of observers. The team of observers shall be composed of the forces and commanders from the facilitators as well as representatives of both sides.

3.3 DEMILITARIZATION shall be completed within the time-frame of one month.

3.4 The issue of civil administration in populated demilitarized areas shall be addressed through appropriate ad hoc arrangements that will be put in place for the interim period.

3.5 When the INTERIM period comes to an end following the completion of the demarcation of the entire boundary between the two countries, the LEGITIMATE AUTHORITIES shall regain full jurisdiction over their respective SOVEREIGN TERRITORIES.

3.6 The details regarding DEMILITARIZATION and its implementation modalities shall be included in the main agreement as annex.

4. A full INVESTIGATION of the incident of May 6 1998 shall be conducted in tandem with the demilitarization process.

5. This COMPREHENSIVE agreement, signed by both parties, shall be deposited in the UN and OAU as a legal agreement so as to ensure its binding nature.

The three onflict zones in the Eritrean - Ethiopian border conflict:

- The Badme region (the main area of conflict in the war) in the western border region

- The Tsorona-Zalambessa area in the central border area

- The Bure area in the eastern border region

Text of Agreement Between Eritrea and Ethiopia signed in Algiers, 12 December 2000

Agreement between the Government of the State of Eritrea and the Government of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia

The Government of the State of Eritrea and the Government of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (the "parties"),

Reaffirming their acceptance of the Organization of African Unity ("OAU") Framework Agreement and the Modalities for its Implementation, which have been endorsed by the 35th ordinary session of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government, held in Algiers, Algeria, from 12 to 14 July 1999,

Recommitting themselves to the Agreement on Cessation of Hostilities, signed in Algiers on 18 June 2000,

Welcoming the commitment of the OAU and the United Nations, through their endorsement of the Framework Agreement and Agreement on Cessation of Hostilities, to work closely with the international community to mobilize resources for the resettlement of displaced persons, as well as rehabilitation and peacebuilding in both countries,

Have agreed as follows:

Article 1

1. The parties shall permanently terminate hostilities between themselves. Each party shall refrain from the threat or use of force against the other.

2. The parties shall respect and fully implement the provisions of the Agreement on Cessation of Hostilities.

Article 2

1. In fulfilling their obligations under international humanitarian law, including the 1949 Geneva Conventions relative to the protection of victims of armed conflict ("1949 Geneva Conventions"), and in cooperation with the International Committee of the Red Cross, the parties shall without delay, release and repatriate all prisoners of war.

2. In fulfilling their obligations under international humanitarian law, including the 1949 Geneva Conventions, and in cooperation with the International Committee of the Red Cross, the parties shall without delay, release and repatriate or return to their last place of residence all other persons detained as a result of the armed conflict.

3. The parties shall afford humane treatment to each other's nationals and persons of each other's national origin within their respective territories.

Article 3

1. In order to determine the origins of the conflict, an investigation will be carried out on the incidents of 6 May 1998 and on any other incident prior to that date which could have contributed to a misunderstanding between the parties regarding their common border, including the incidents of July and August 1997.

2. The investigation will be carried out by an independent, impartial body appointed by the Secretary General of the OAU, in consultation with the Secretary General of the United Nations and the two parties.

3. The independent body will endeavor to submit its report to the Secretary General of the OAU in a timely fashion.

4. The parties shall cooperate fully with the independent body.

5. The Secretary General of the OAU will communicate a copy of the report to each of the two parties, which shall consider it in accordance with the letter and spirit of the Framework Agreement and the Modalities.

Article 4

1. Consistent with the provisions of the Framework Agreement and the Agreement on Cessation of Hostilities, the parties reaffirm the principle of respect for the borders existing at independence as stated in resolution AHG/Res. 16(1) adopted by the OAU Summit in Cairo in 1964, and, in this regard, that they shall be determined on the basis of pertinent colonial treaties and applicable international law.

2. The parties agree that a neutral Boundary Commission composed of five members shall be established with a mandate to delimit and demarcate the border based on pertinent colonial treaties (1900, 1902 and 1908) and applicable international law. The Commission shall not have the power to make decisions ex aequo et bono.

3. The Commission shall be located in the Hague.

4. Each party shall, by written notice to the United Nations Secretary General, appoint two commissioners within 45 days from the effective date of this agreement, neither of whom shall be nationals or permanent residents of the party making the appointment. In the event that a party fails to name one or both of its party-appointed commissioners within the specified time, the Secretary-General of the United Nations shall make the appointment.

5. The president of the Commission shall be selected by the party-appointed commissioners or, failing their agreement within 30 days of the date of appointment of the latest party-appointed commissioner, by the Secretary-General of the United Nations after consultation with the parties. The president shall be neither a national nor permanent resident of either party.

6. In the event of the death or resignation of a commissioner in the course of the proceedings, a substitute commissioner shall be appointed or chosen pursuant to the procedure set forth in this paragraph that was applicable to the appointment or choice of the commissioner being replaced.

7. The UN Cartographer shall serve as Secretary to the Commission and undertake such tasks as assigned to him by the Commission, making use of the technical expertise of the UN Cartographic Unit. The Commission may also engage the services of additional experts as it deems necessary.

8. Within 45 days after the effective date of this Agreement, each party shall provide to the Secretary its claims and evidence relevant to the mandate of the Commission. These shall be provided to the other party by the Secretary.

9. After reviewing such evidence and within 45 days of its receipt, the Secretary shall subsequently transmit to the Commission and the parties any materials relevant to the mandate of the Commission as well as his findings identifying those portions of the border as to which there appears to be no dispute between the parties. The Secretary shall also transmit to the Commission all the evidence presented by the parties.

10. With regard to those portions of the border about which there appears to be controversy, as well as any portions of the border identified pursuant to paragraph 9 with respect to which either party believes there to be controversy, the parties shall present their written and oral submissions and any additional evidence directly to the Commission, in accordance with its procedures.

11. The Commission shall adopt its own rules of procedure based upon the 1992 Permanent Court of Arbitration Option Rules for Arbitrating Disputes Between Two States. Filing deadlines for the parties' written submissions shall be simultaneous rather than consecutive. All decisions of the Commission shall be made by a majority of the commissioners.

12. The Commission shall commence its work not more than 15 days after it is constituted and shall endeavor to make its decision concerning delimitation of the border within six months of its first meeting. The Commission shall take this objective into consideration when establishing its schedule. At its discretion, the Commission may extend this deadline.

13. Upon reaching a final decision regarding delimitation of the borders, the Commission shall transmit its decision to the parties and Secretaries General of the OAU and the United Nations for publication, and the Commission shall arrange for expeditious demarcation.

14. The parties agree to cooperate with the Commission, its experts and other staff in all respects during the process of delimitation and demarcation, including the facilitation of access to territory they control. Each party shall accord to the Commission and its employees the same privileges and immunities as are accorded to diplomatic agents under the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations.

15. The parties agree that the delimitation and demarcation determinations of the Commission shall be final and binding. Each party shall respect the border so determined, as well as the territorial integrity and sovereignty of the other party.

16. Recognizing that the results of the delimitation and demarcation process are not yet known, the parties request the United Nations to facilitate resolution of problems which may arise due to the transfer of territorial control, including the consequences for individuals residing in previously disputed territory.

17. The expenses of the Commission shall be borne equally by the two parties. To defray its expenses, the Commission may accept donations from the United Nations Trust Fund established under paragraph 8 of Security Council Resolution 1177 of 26 June 1998.

Article 5

1. Consistent with the Framework Agreement, in which the parties commit themselves to addressing the negative socio-economic impact of the crisis on the civilian population, including the impact on those persons who have been deported, a neutral Claims Commission shall be established. The mandate of the Commission is to decide through binding arbitration all claims for loss, damage or injury by one Government against the other, and by nationals (including both natural and juridical persons) of one party against the Government of the other party or entities owned or controlled by the other party that are (a) related to the conflict that was the subject of the Framework Agreement, the Modalities for its Implementation and the Cessation of Hostilities Agreement, and (b) result from violations of international humanitarian law, including the 1949 Geneva Conventions, or other violations of international law. The Commission shall not hear claims arising from the cost of military operations, preparing for military operations, or the use of force, except to the extent that such claims involve violations of international humanitarian law.

2. The Commission shall consist of five arbitrators. Each party shall, by written notice to the United Nations Secretary General, appoint two members within 45 days from the effective date of this agreement, neither of whom shall be nationals or permanent residents of the party making the appointment. In the event that a party fails to name one or both of its party-appointed arbitrators within the specified time, the Secretary-General of the United Nations shall make the appointment.

3. The president of the Commission shall be selected by the party-appointed arbitrators or, failing their agreement within 30 days of the date of appointment of the latest party-appointed arbitrator, by the Secretary-General of the United Nations after consultation with the parties. The president shall be neither a national nor permanent resident of either party.

4. In the event of the death or resignation of a member of the Commission in the course of the proceedings, a substitute member shall be appointed or chosen pursuant to the procedure set forth in this paragraph that was applicable to the appointment or choice of the arbitrator being replaced.

5. The Commission shall be located in The Hague. At its discretion it may hold hearings and conduct investigations in the territory of either party, or at such other location as it deems expedient.

6. The Commission shall be empowered to employ such professional, administrative and clerical staff as it deems necessary to accomplish its work, including establishment of a Registry. The Commission may also retain consultants and experts to facilitate the expeditious completion of its work.

7. The Commission shall adopt its own rules of procedure based upon the 1992 Permanent Court of Arbitration Option Rules for Arbitrating Disputes Between Two States. All decisions of the Commission shall be made by a majority of the commissioners.

8. Claims shall be submitted to the Commission by each of the parties on its own behalf and on behalf of its nationals, including both natural and juridical persons. All claims submitted to the Commission must be filed no later than one year from the effective date of this agreement. Except for claims submitted to another mutually agreed settlement mechanism in accordance with paragraph 17 or filed in another forum prior to the effective date of this agreement, the Commission shall be the sole forum for adjudicating claims described in paragraph 1 or filed under paragraph 9 of this Article, and any such claims which could have been and not submitted by that deadline shall be extinguished, in accordance with international law.

9. In appropriate cases, each party may file claims on behalf of persons of Eritreans or Ethiopian origin who may not be its nationals. Such claims shall be considered by the Commission on the same basis as claims submitted on behalf of that party's nationals.

10. In order to facilitate the expeditious resolution of these disputes, the Commission shall be authorized to adopt such methods of efficient case management and mass claims processing as it deems appropriate, such as expedited procedures for processing claims and checking claims on a sample basis for further verification only if circumstances warrant.

11. Upon application of either of the parties, the Commission may decide to consider specific claims, or categories of claims, on a priority basis.

12. The Commission shall commence its work not more than 15 days after it is constituted and shall endeavor to complete its work within three years of the date when the period for filing claims closes pursuant to paragraph 8.

13. In considering claims, the Commission shall apply relevant rules of international law. The Commission shall not have the power to make decisions ex aequo et bono.

14. Interest, costs and fees may be awarded.

15. The expenses of the Commission shall be borne equally by the parties. Each party shall pay any invoice from the Commission within 30 days of its receipt.

16. The parties may agree at any time to settle outstanding claims, individually or by categories, through direct negotiation or by reference to another mutually agreed settlement mechanism.

17. Decisions and awards of the Commission shall be final and binding. The parties agree to honor all decisions and to pay any monetary awards rendered against them promptly.

18. Each party shall accord to members of the Commission and its employees the privileges and immunities that are accorded to diplomatic agents under the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations.

Article 6

1. This agreement shall enter into force on the date of signature.

2. The parties authorize the Secretary General of the OAU to register this agreement with the Secretariat of the United Nations in accordance with article 102(1) of the Charter of the United Nations.

DONE at _____ on the _____ day of November, 2000, in duplicate in the English language.

For the Government of the State of Eritrea: For the Government of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia:

For the Government of the State of Eritrea:

_______________

For the Government of the Federal

Democratic Republic of Ethiopia:_______________

Isaias Afwerki

Meles Zenawi

Ethiopia-Eritrea:

background to the conflict

Published By Le Monde diplomatique

Two years ago the two governments set up a secret committee to decide what was to be done about the disputed areas. It was able to achieve very little apart from noting the contentious points. On paper, the Eritreans have a better case. In the declarations of 14 and 20 May 1998 they are only claiming the colonial border, in other words the line drawn at the beginning of this century between the kingdom of Italy and the Ethiopian empire. The frontier was defined by a series of international agreements after the defeat of the Italian troops in Aduwa in 1896, based on a tripartite treaty which Britain, Italy and Ethiopia signed on 15 May 1902. This defines the western and central part of the border where the recent incidents occurred.

From west to east, starting at Khor Um Hagger on the Sudanese border, the frontier line follows the river Tekezze (Setit) to the point at which it meets the river Maieteb, then runs in a straight line to the river Mereb in the north, at its confluence with the Ambessa. After that it runs along the Mereb, crossing most of the central plateau, then along its tributary, the Melessa, to the east and finally along the river Muna.

There is no indication that the Ethiopian government is disputing this line, which has remained unchanged since 1902. It appears on all Ethiopian official and tourist maps, including those given to foreign ambassadors by the foreign minister in Addis Ababa on 19 May this year.

The Eritreans, however, are accusing the Tigrayan local authorities of using another map published in the Tigrayan capital, Mekele, in 1997. In this map, small enclaves to the north of the Melessa-Muna line (Tserona, Belissa, Alitenia) and a larger enclave to the west of the straight line between Tekezze and Mareb, in Badme, are shown as part of Ethiopia. It was here that the trouble flared early in May.

In 1902 the Badme region was virtually uninhabited. At the time, Badme was the name of a plain which the border ran across. Situated below the Abyssinian plateau, it is an extension of the Eritrean region of Gash-Setit, a semi-arid lowland area stretching westward as far as Sudan.

In the last few decades, the area has gradually been settled by farmers from the Eritrean and Tigrayan high plateaus and the Kunamas, the earliest inhabitants, have villages there. When the United Nations federated Eritrea with Ethiopia in 1952, the 1902 line became irrelevant. Ras Mengesha, the Tigrayan ruler, paid very little attention to it, developing agricultural settlements administered by the Tigrayan district of Shire on both sides of the border. Since then, the area has been periodically disputed. In 1976 and 1981, for example, it was the scene of clashes between the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) and the Tigrayan People's Liberation Front (TPLF).

The two rebel groups united to fight against Colonel Mengistu's government and the problem was temporarily shelved after the Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF) took control of the Eritrean resistance. In 1987 the Mengistu government further complicated the issue by changing administrative boundaries. At the end of the war, in 1991, the Tigray still regarded the area as theirs, although it was patrolled by soldiers from both countries. The intergovernmental committee was then faced with a situation that was very clear on paper - the "colonial" borders were officially accepted by both states, as well as by the Organization of African Unity and the United Nations - but highly complex in practice, especially since all the Kunama tribes' territory had been incorporated into Eritrea under the 1902 treaty and the Kunamas clearly took very little notice of an imaginary straight line drawn across the plain.

In the central border region, the small enclaves already claimed by the TPLF program in the 1970s had been in the same ambiguous position since 1991. But at least this western and central part of the Eritrean-Ethiopian border is clearly defined on paper, which is more than can be said of the line to the east, along the Red Sea, separating the Eritrean Dankalia region from the Ethiopian Afar region as far as Djibouti. According to the 1908 treaty in which this border was established, it was supposed to follow the coastline at a distance of 60 kilometers and a joint committee was to mark it out later in the field. But when the UN opened the files forty years later, they found no record of a demarcation.

The boundaries between the former Italian colony and Ethiopia are fairly well known locally, but they are still disputed in a few places, notably Bada Adi Murug, which the Ethiopians occupied last year. The border runs right through a small fertile region overlooking the Gulf of Thio in the distance, to Burie, on the road to Assab.

J.-L. P.

Translated by Lorna Dale

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ) 1998 Le Monde diplomatique

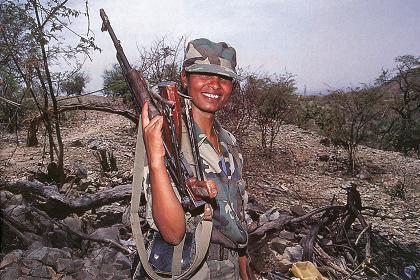

23 year old female Eritrean soldier Asmert who regrets that the

world gives so little attention to this war (Photo: Arnold Karskens).